Al-Andalus: The Birth of Muslim Spain

Modern day Andalucia is defined by a unique culture and identity - visible in both its traditions and its architecture. It is a land which has been shaped by immmigrants and power struggles for over 3,000 years. Recorded history began in 1200 BCE, as Phoenician traders were the first group to write about the Iberian peninsula, and they established the coastal trading city of Cadiz.

In the next thousand years, the region was inhabited by Greeks and then conquered by the Romans. After the Romans were thrown out by the Vandals and the Visigoths, there was a period of stasis, sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages. Then, in the early 8th century, the most important and influential era began in the history of southern Spain - instigated by a muslim exile from Syria.

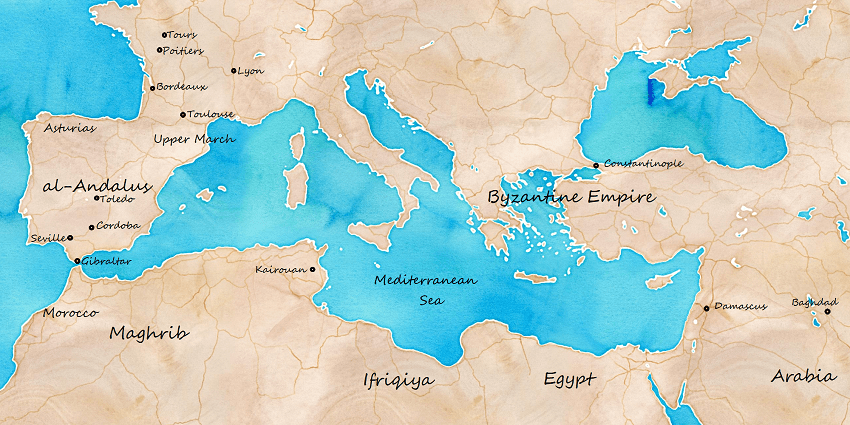

In this article we will look at the early history of al-Andalus. How did muslim Spain come in to being - and what were the consequences of this. The map below show the main locations involved in the story, so you can refer back to this to see the geography of the conquest. Click on the map to enlarge it in a new screen.

When Muhammad died in 632 there was a succession crisis, which ultimately resulted in three successors (caliphs) being named. These were the Umayyads - part of the Quaraysh tribe and members of Muhammad's inner circle. The Umayyads established a base in Damascus and expanded the reach of Islam rapidly - quickly taking hold in Syria, Israel, part of Turkey and much of North Africa. The spread through North Africa in particular was precipitated by a rivalry with the Byzantine empire based in Constantinople, and a desire to conquer an important part of the Mediterranean.

Tariq defeated the Visigothic King Roderic at the battle of Guadalete and headed north, taking most of Spain as he went. By 716, Tariq's boss Musa had re-taken control of proceedings, and his army had reached the edge of the Pyrenees. In 717, he crossed the Pyrenees and entered modern day France. After sacking Lyon and moving into Burgundy, Musa's forces faced their first significant setback in 721 when they were defeated at Toulouse by the Aquitanian ruler, King Odo. By this point, Musa's Muslim army was stretched thin, as many of his troops (particularly the Berbers) had decided to settle in al-Andalus, so they largely retreated back to the Iberian peninsula.

By the 730s, the Muslims had consolidated their hold over Spain - known as Al-Andalus. So, in 732, the governor sent a large army north into Aquitaine to fight King Odo once again. This time the Muslims were victorious, taking the city of Bordeaux. Continuing north, the Muslim army headed towards the important city of Tours, where they planned to sack the rich monastery. They were, however, intercepted outside of Poitiers, where they were defeated by the Frankish King - Charles Martel.

Charles Martel is often portrayed as being the founder of modern day France, thanks to his role in defeating the invading Muslims forces, and in safeguarding the role of Christianity in the Frankish kingdoms. Indeed, Charles Martel's grandson - King Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, is also credited with starting the Christian reconquest against the Iberian lands (despite being defeated at the battle of Roncesvalles in 778, Charlemagne did manage to set up a buffer zone in north-eastern Spain between France and Al-Andalus - this zone later evolved into what is now modern day Catalonia). Most modern historians, however, reject this interpretation as little more than a 'nation building myth'. The Muslim force was almost certainly just looking to sack the monastery before retreating back to Al-Andalus with pockets full of gold and silver. They had neither the manpower nor a secure enough grip on their own lands to be looking to conquer a region as large and potentially hostile as France was at this time.

The same can not be said of the situation in Arabia which, by 750, was in open revolt. The Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids, a clan based in Persia, and were hunted down as they tried to escape from their Damascus capital. All but one of the Umayyad heirs were killed. The lone survivor, Abd al-Rahman, made a daring escape. He swam across the Euphrates River and, with the support of a few soldiers and family members, he stealthy moved through Egypt and Ifriqiya (Libya), before reaching the relative safe haven of Kairouan (Tunisia) - far from the tentacles of Abbasid power.

Abd al-Rahman then began to plan how he could re-establish power, something that his Umayyad heritage demanded. Politically divided and also far from the hostile Abbasids (who had established a new capital and caliphate in Baghdad), Al-Andalus looked to be the best bet. After a few years spent analysing the situation, in 755, Abd al-Rahman landed on the Iberian peninsula. In May 756, along with his small but loyal army, Abd al Rahman defeated the local governor and was declared Amir (prince) of al-Andalus in Cordoba's mosque.

He also began the process of decreasing the reliance on the Visigothic nobility and the Catholic church. He built mosques and created a state bureaucracy, including a judiciary, which was dominated by Muslims. However, Abd al-Rahman's rule was not one characterized by jihad (holy war), rather, it was one of consolidation. By the time of his death in 788, he had conquered most of the Iberian peninsula, but had also signed peace treaties with the Christian Asturias Kingdom in Northern Spain, and retreated from other mountainous areas, such as the Pyrenees, that would have been too demanding to hold.

By Abd al-Rahman's death, most of the population in al-Andalus were still Christians. There were no mass forced conversions to Islam and, of those Christians who had converted, many (particularly the Visigothic elite) did so for political reasons, in an effort to preserve their own power and status. Muslim strongholds were the cities, particularly in the south of the country (Seville, Cordoba and Toledo being the three largest), while Christians dominated the rural areas and the north of the peninsula. There was also a small Jewish presence on the peninsula, but, as a religious group, they are almost invisible in the historical records from the time.

Cordoba was particularly important as the capital. Thanks to the dynasty that Abd al-Rahman had set in motion - making his sons the governors of key cities and military commanders, as well as promoting his loyal supporters to positions of influence - the Umayyads were able to dominate the political and cultural landscape of the Iberian peninsula for the best part of three centuries. During this time, Cordoba grew to become one of the greatest and most important cities in the world and al-Andalus began to revolutionize science, culture and philosophy, which had taken a back seat in Europe since the fall of Rome.

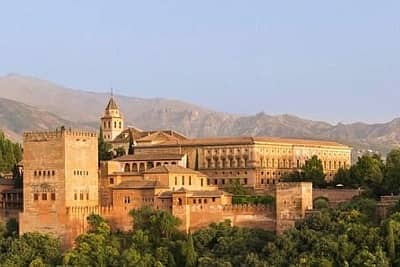

To find out more about the incredible history of al-Andalus, check out our city guides to Seville, Cordoba and Granada, as well as our detailed article on the Medina Azahara palace complex.

If you would like to discover the region first hand, join us on our guided cycling holiday through the region. Led by a qualified historian, this trip visits the most interesting historic sites from across various eras, all while riding through the stunning landscapes of southern Spain.

We also run a Self-Guided cycling holiday from Seville to Granada. You can find full details of the itinerary and tour dates by following the links below.

In the next thousand years, the region was inhabited by Greeks and then conquered by the Romans. After the Romans were thrown out by the Vandals and the Visigoths, there was a period of stasis, sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages. Then, in the early 8th century, the most important and influential era began in the history of southern Spain - instigated by a muslim exile from Syria.

In this article we will look at the early history of al-Andalus. How did muslim Spain come in to being - and what were the consequences of this. The map below show the main locations involved in the story, so you can refer back to this to see the geography of the conquest. Click on the map to enlarge it in a new screen.

The Early Years of Islam

Islam essentially became a religion during the life of Muhammad in the early part of the 7th century. Unlike Christianity, which began as a subversive and underground movement, Islam was political and social from its beginning. It quickly took hold among many people in the Byzantine and Persian Empires, which were politically unpopular with many of their subjects, and the new religion was promoted by nomadic warrior leaders in Arabia - particularly the Bedouain.When Muhammad died in 632 there was a succession crisis, which ultimately resulted in three successors (caliphs) being named. These were the Umayyads - part of the Quaraysh tribe and members of Muhammad's inner circle. The Umayyads established a base in Damascus and expanded the reach of Islam rapidly - quickly taking hold in Syria, Israel, part of Turkey and much of North Africa. The spread through North Africa in particular was precipitated by a rivalry with the Byzantine empire based in Constantinople, and a desire to conquer an important part of the Mediterranean.

Crossing the Mediterranean & Early Conquests

During the early part of the 8th century, Musa ibn Nusayr took Morocco on behalf of the Umayyad caliphs, with great support from local Berber tribes who largely resided in what is modern day Morocco and Algeria. Shortly after conquering Morocco, in 711, the Muslims crossed the Mediterranean and landed at Gibraltar. This invasion force was led by a General of Musa named Tariq ibn Ziyad (the name 'Gibraltar' actually comes from the Arabic Jabal Tariq - meaning 'Tariq's mountain').Tariq defeated the Visigothic King Roderic at the battle of Guadalete and headed north, taking most of Spain as he went. By 716, Tariq's boss Musa had re-taken control of proceedings, and his army had reached the edge of the Pyrenees. In 717, he crossed the Pyrenees and entered modern day France. After sacking Lyon and moving into Burgundy, Musa's forces faced their first significant setback in 721 when they were defeated at Toulouse by the Aquitanian ruler, King Odo. By this point, Musa's Muslim army was stretched thin, as many of his troops (particularly the Berbers) had decided to settle in al-Andalus, so they largely retreated back to the Iberian peninsula.

By the 730s, the Muslims had consolidated their hold over Spain - known as Al-Andalus. So, in 732, the governor sent a large army north into Aquitaine to fight King Odo once again. This time the Muslims were victorious, taking the city of Bordeaux. Continuing north, the Muslim army headed towards the important city of Tours, where they planned to sack the rich monastery. They were, however, intercepted outside of Poitiers, where they were defeated by the Frankish King - Charles Martel.

Charles Martel is often portrayed as being the founder of modern day France, thanks to his role in defeating the invading Muslims forces, and in safeguarding the role of Christianity in the Frankish kingdoms. Indeed, Charles Martel's grandson - King Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, is also credited with starting the Christian reconquest against the Iberian lands (despite being defeated at the battle of Roncesvalles in 778, Charlemagne did manage to set up a buffer zone in north-eastern Spain between France and Al-Andalus - this zone later evolved into what is now modern day Catalonia). Most modern historians, however, reject this interpretation as little more than a 'nation building myth'. The Muslim force was almost certainly just looking to sack the monastery before retreating back to Al-Andalus with pockets full of gold and silver. They had neither the manpower nor a secure enough grip on their own lands to be looking to conquer a region as large and potentially hostile as France was at this time.

Turmoil in Arabia - A Daring Escape

By the mid 8th century, al-Andalus was firmly under Muslim control; however, that is not to say that it was united. There was much infighting, particularly between the Arab Muslims and the Berbers; the latter feeling that they were treated as second class citizens, despite being hugely important in the conquests. There was also some trouble from the remaining Visigothic nobility. The Muslims, to a large extent, were reliant on Visigothic networks and institutions for many tasks of state administration. In particular, the Catholic church was instrumental in collecting taxes for the Muslim regime, and so had some leverage to make demands from, or cause trouble to, the Muslims. There were occasional outbursts of violence, for example Musa killing all the Visigothic nobles in the former capital city of Toledo. However, for the most part, the tension was left simmering underneath the surface.The same can not be said of the situation in Arabia which, by 750, was in open revolt. The Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids, a clan based in Persia, and were hunted down as they tried to escape from their Damascus capital. All but one of the Umayyad heirs were killed. The lone survivor, Abd al-Rahman, made a daring escape. He swam across the Euphrates River and, with the support of a few soldiers and family members, he stealthy moved through Egypt and Ifriqiya (Libya), before reaching the relative safe haven of Kairouan (Tunisia) - far from the tentacles of Abbasid power.

Abd al-Rahman then began to plan how he could re-establish power, something that his Umayyad heritage demanded. Politically divided and also far from the hostile Abbasids (who had established a new capital and caliphate in Baghdad), Al-Andalus looked to be the best bet. After a few years spent analysing the situation, in 755, Abd al-Rahman landed on the Iberian peninsula. In May 756, along with his small but loyal army, Abd al Rahman defeated the local governor and was declared Amir (prince) of al-Andalus in Cordoba's mosque.

The Shaping of al-Andalus

The al-Andalus emirate which Abd al-Rahman established was politically volatile and needed to be brought under control. The new Amir achieved this through astute political manoeuvres, as well as ruthlessly dealing with any resistance. One of his earliest actions was to welcome the remnants of the Umayyad family (and their sympathizers) from across the Arab world and North Africa. He assigned them important positions within the state which, although it alienated some of his early supporters, did help to consolidate his power base.He also began the process of decreasing the reliance on the Visigothic nobility and the Catholic church. He built mosques and created a state bureaucracy, including a judiciary, which was dominated by Muslims. However, Abd al-Rahman's rule was not one characterized by jihad (holy war), rather, it was one of consolidation. By the time of his death in 788, he had conquered most of the Iberian peninsula, but had also signed peace treaties with the Christian Asturias Kingdom in Northern Spain, and retreated from other mountainous areas, such as the Pyrenees, that would have been too demanding to hold.

By Abd al-Rahman's death, most of the population in al-Andalus were still Christians. There were no mass forced conversions to Islam and, of those Christians who had converted, many (particularly the Visigothic elite) did so for political reasons, in an effort to preserve their own power and status. Muslim strongholds were the cities, particularly in the south of the country (Seville, Cordoba and Toledo being the three largest), while Christians dominated the rural areas and the north of the peninsula. There was also a small Jewish presence on the peninsula, but, as a religious group, they are almost invisible in the historical records from the time.

Cordoba was particularly important as the capital. Thanks to the dynasty that Abd al-Rahman had set in motion - making his sons the governors of key cities and military commanders, as well as promoting his loyal supporters to positions of influence - the Umayyads were able to dominate the political and cultural landscape of the Iberian peninsula for the best part of three centuries. During this time, Cordoba grew to become one of the greatest and most important cities in the world and al-Andalus began to revolutionize science, culture and philosophy, which had taken a back seat in Europe since the fall of Rome.

To find out more about the incredible history of al-Andalus, check out our city guides to Seville, Cordoba and Granada, as well as our detailed article on the Medina Azahara palace complex.

If you would like to discover the region first hand, join us on our guided cycling holiday through the region. Led by a qualified historian, this trip visits the most interesting historic sites from across various eras, all while riding through the stunning landscapes of southern Spain.

We also run a Self-Guided cycling holiday from Seville to Granada. You can find full details of the itinerary and tour dates by following the links below.

Spain

Spain